Kaushalya Bannerji

(Excerpt from presentation, Berkshires Women’s History Conference)

copyright 2014

This is a piece whose purpose is to reflect on and pay tribute to the work of Gloria Rolando, whose commitment to Afro-Cuban history and to the notion of culture as resistance to forces of oppression and hegemonic amnesia, make her films both contextually important and necessary; as histories whose details and meanings lie unexplored— are revealed— to have great importance in the project of nation-building and its connection to national memory.

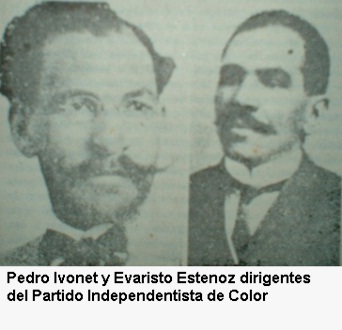

For example, Gloria’s commitment to unearthing the truth about the PIC — the western hemisphere’s first black party in 1908-1912, the Partido Independiente de Color (PIC)— and by extension, painting a picture of black every day life, has much to teach us. This commitment has been an outgrowth of her work on Assata Shakur and the Black Panther Party immediately preceding her research on the PIC since the late 1990s. Her 2001 Roots of My Heart and the current trilogy of films, 1912: Breaking the Silence: on the PIC— are only part of her vast body of work as Director and Assistant Director at ICAIC and Imagenes del Caribe.

Her work is especially crucial in my view, as we see the resurgence of a racialized tourist industry in Cuba where the old trope of “good appearance” is a mask for the demands for white and light-skinned representatives of Cuba to interact with the foreign public, while cleaners, manual labourers, gardeners and grill cooks, augmented by some entertainment staff are comprised of black Cubans. This 2 tiered hierarchy is so apparent to the outsider, that many do not realize what an achievement it actually had been to extend free public education, health care and public infrastructure and goods and services to blacks and whites alike, through the heady days of the Revolution which came to an abrupt halt with the demise of the Soviet Union. Today, remittances also separate white and black populations in Cuba as the vast majority of migrants who have left the island and are in a position to send money back to the island are of white Cuban background.

George Lamming, in the introduction to Walter Rodney’s “History of the Guyanese Working Peoples”, spoke of the ways in which colonized peoples in the Caribbean and the Americas “re-humanized” the landscape of dispossession and colonial violence through “human sensuous activity” (Marx)— that is— activity of the senses and material life. The transformative power of action whether in the cane fields or the construction of plantations, railroads or cultural/social practices, is dual-edged in this sense— labour transforms the individual who performs it while simultaneously transforming the material environment and social relations.

Thus, Gloria’s work is part of a centuries old practice of “re-humanization” as resistance. As a people’s historian who presents the past as the basis for learning and reflection, Gloria’s documentaries paint a rich picture of a truly diverse Caribbean, in which resistance to hegemony and homogeneity are portrayed by her subjects, whether Jamaican descendants in Ciego de Avila or Cuban fisher people in the Caiman islands, or the FBI’s most wanted female “terrorist”, Assata Shakur.

This resistance that Gloria participates in comes from a tradition of rich intellectual and socio-economic analyses as well as social activism provided by Afro-descended peoples between and across the Caribbean and Americas. In the era of the early twentieth century, or the Neo-Republic in Cuba, when the PIC was struggling to gain a parliamentary voice for Afro-descended peoples, Du Bois was active in the United States, Juan Gualberto Gomez and Rafael Serra were expressing their views in Cuba and the recent migration and mixing of Caribbean people in the U.S. was laying the seeds for writers like Claude MacKay, Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes to emerge, giving flesh and meaning to Afro-descended viewpoints, while ideas of racial mixture and purity were hotly debated, for example, in Brazil’s “national imaginary.”

Cuba’s own nineteenth century national novel and zarzuela, “Cecilia Valdes”, speaks to the ever-present anxieties of race, gender and class that haunt colonial societies— both settler and extractive colonies- as they navigated their way through centuries of enslavement and the buying and selling of black peoples into the realm of “free” wage labour.

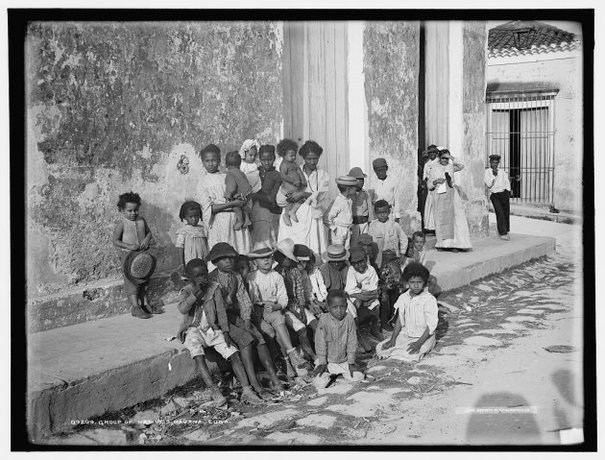

I aim to give a sense of the context in which the PIC had emerged, a mere 20 years after Emancipation, an era in which ex-slaves were thrown into the social relations of free- wage labour that were skewed against them through a number of legislative, regulatory and white vigilantist barriers. It was an era characterized by the U.S. occupation of Cuba and rapid ownership of its lands while the confluence of both imperialist and national elite interests lay in maintaining white supremacy for economic profit and social denial of civil rights to blacks.

I imagine that for the leadership of the PIC, a constellation of state forces— informal and political on one hand, and the regulation of cultural practices such as the banning of Afro-Cuban public gatherings and prohibiting the playing of congas and other percussive instruments on the other, (1906-13) must have propelled them to a self-reflective mode with regard to the social and political role of the Afro-Cuban population. Certainly, the first coordinating body of the different black organizations, the Directory of the Associations of People of Colour, headed by Juan Gualberto Gomez, had as its aim, not only the social integration of Afro-Cubans, but also situated its thinking in terms of classical liberal philosophy.

Historians such Aline Helg and Ada Ferrer show the exclusion of anti-Spain liberationists of African descent in posts that lent themselves to social mobility in a post-Independence context— both civil and military posts. Paralyzed in their hopes for a more just, inclusive and equal world, the leadership of the PIC, which had paid its dues in the liberation army against Spain (an army, some historians say, that counted on more than 85 percent Afro-Cuban fighters) began to organize based on a platform of social reform.

Formal and informal segregation in employment, indirect taxation on Cabildos de Nacion through various cumbersome municipal regulations; an education system based on supposedly “civilizing” values; an extremely low participation in voting due to high financial requirements all served up an ensemble of factors whose function and objective was social alienation for blacks. Perhaps because many other professions would not let them in, the end of the nineteenth century was witness to that fact that 50 percent of musicians on the island were black. Segregation indeed has played a great part in the Cuban music we enjoy today!

Stevedores and dockworkers were also predominantly urban Afro-Cuban occupations as well as small artisan and skilled trades such as building.

We can also see how legal measures were used to affect the economic opportunities available for this demographic sector, which in the early twentieth century comprised 30 percent of the population of Cuba.

Simultaneously, tensions between distinct factions of the colonial and neo-colonial elites in Cuba created an atmosphere in which the black population was seen as a “problem” for the hegemonic class. Much has been written about the Cuban’s state’s subsidized immigration policies for Spanish migrants to restore what they saw as “racial equilibrium” in favour of white supremacy to the island in those years (Gott). Laws proliferated in favour of white immigration and this moment saw an influx of Canary islanders and other impoverished Spaniards. More whites came to the island in this period than ever before, including the family of Fidel and Raul Castro.

Disappointed by the lack of action on the part of the Liberal Party on questions of racial inequality and by the presence of the United States in Cuba, the men of the PIC also confronted the myth of racial equality (de la Fuente). According to this hegemonic idea, discrimination did not exist in Cuba based on race and colour. Jose Marti’s belief in a colour-blind and equal Cuba where black and white shared in the benefits of a post-Independence state and society was part of both ideology and hopes for a future.

And if, for some reason, the black community was found to inhabit the indices of poverty and marginality in high numbers, they felt, this was simply the sign of African inferiority. Hidden away in these platitudes were other sinister myths of black malevolence found in moral panics (Jock Young) generated by the press in newspapers such as El Dia. and El Heraldo de la Marina etc. These myths , at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth, focussed on “witchcraft” — the supposed sphere of Afro-Cubans. Other myths of black male sexual avariciousness, and the innate sexual availability of the black woman combined gruesomely with the meta-anxiety of the Caribbean elites— that of black uprising, exemplified by the Haitian revolution between 1791-1804, ((Rafael Duharte Jiménez “Dos Viejos Temores de Nuestro Pasado”, Seis Ensayos de Interpretación Histórica, Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente 1983, 83-100 y Aline Helg, 6-7).

The leaders of the PIC such as Evaristo Estenoz, Gregorio Surin and later, Pedro Ivonnet among others, fought these social and material prejudices with a republicanism that emphasized belief in the concepts of “man” and “citizen”. In my view, their struggle for anti-racist equality and dignity was rooted in the failure of classic liberalism to deal with world colonialisms. So important was the notion of the universal in hegemonic thinking, that the particular was demeaned and made invisible. Within the “Universal”, as colony after colony would discover, dwelt the “Master”.

All twentieth century anti-discrimination struggles, have at their heart, the challenge of redefining what it means to be human and have been awoken by the promise— a false promise— of classical liberalism’s “universality”. And this challenge of taking or re-taking public space, social, economic and political participation, as well as cultural participation signalled for the PIC, not the emergence of a black nationalism, but rather a black movement toward equal and proportionate representation and participation and equal access to opportunities, procedures and mechanisms of material and intellectual integration.

I am going to end with some ideas about the political platform of the PIC, because i think it is worth the effort to recognize that different roads can bring us to the same place. What distinguishes the PIC is the unique character of its call to arms which at its time demonstrated an understanding of the ways in which race and class make up colonial social organization, reinforcing the class character of social positions while racializing occupations and access to social goods and services, including “justice”.

For example, the PIC undertook political activism using public expression, creating their own newspaper and through electoral processes and structures. Like many other Afro-descendents in the Americas, the Independents linked their republican and democratic nationalism to their efforts to attain social mobility and civil rights as men and women “of colour”, but they had to overcome a racism that crossed both neo-colonial and national bourgeoisies that denied their claim to be part of the “universal” dreamt of by Rousseau. They tried to do this through theoretical battles and impassioned philosophical pleas, weapons available to them within the norms of the existing system. Paraphrasing Sojourner’s Truth’s eloquent and powerful speech challenging the hegemonic concept of the suffragette universal at a cost to black women’s particularized experiences, “Ain’t I a Woman?” given at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio sixty years earlier, the Independents asked Cuba” Ain’t I a man?”

The Independents identified as Cubans, and fought for a sovereign and equal republic, vigorously defending employment for native-born Cubans, as well as a non-racial immigration policy for Cuba. As a political party they were the first to institute the call for the 8 hour work day and for workplace tribunals to air grievances between workers and bosses; they called for re-distribution of state-owned lands and urged that those who worked the land be given shares in it. They called for free universal education at all levels and state control of education (which was fragmented, privatized, and race-based at that point). They demanded changes to the administration of justice and in the carceral regime in favour of education and rehabilitation of the poor and other measures that in real life actually transcended racial questions. Political demands, we see that re-emerged in the 1930s and then the 1950s with the arrival of Fidel and the 26th of July Movement.

The Independents were among those Cubans who criticized U.S. imperialism in their country, and the leasing of Guantanamo as a U.S. military base and the virulent racism they brought with them

(Fernando Martínez Heredia, “Centenario de la Fundación del Partido Independiente de Color, Cubarte, 05.02.08).

Not many people know about the genocide against the Afro-descended population that occurred in Cuba in 1912, due to elite fears of a black revolution in Cuba. The massacre of 6000 people in that year through state and vigilante collaboration, effectively stopped any dialogue on the damaging effects of racism on social development, a dialogue that has not even been officially raised in the post-Batista Cuba until now.

I conclude with the words of Gloria Rolando herself ( Cuban women filmmakers, U.S. Showcase and Interview with Gloria Rolando, Black Film archive, March 8 2013)

“My grandmother, whose hands I never will forget, used to work as a domestic in the houses of other people. She was a character; she’d never talk about age, she’d talk about life. She told me how in Santa Clara in the 30s and 40s black people would walk around the park while white people would walk inside the park; it was the custom of that time. She told me about the Union Fraternal, the society for black people in Havana, and another black society for those who were doctors or lawyers or teachers. I remember that she used to say, “Maybe you will attend the Club Athenas ( the most important Club in Havana for black professionals and the middle class) because you have your degree, you graduated, you are a professional.” In school, though, I never heard about this kind of history”… It has been Gloria’s passion for bringing such histories to both Cuban and international audiences that has fuelled her work, a commitment to give a voice to those who have often spoken but not been heard.

Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gloria_Rolando

http://www.afrocubaweb.com/gloriarolando/gloriarolando.htm

Many Many Thanks! Mil Gracias! Estoy aprendiendo a bloguear y parece que nuestros temas coinciden! Chequealo de vez en cuando!

LikeLike